Heat exchangers are the unsung heroes behind efficient energy usage in countless industries—from power plants and chemical refineries to air conditioning and food processing. But without a clear understanding of how they work, engineers risk underutilizing them or designing inefficient systems. Fortunately, while their designs may vary, all heat exchangers share a common operating principle rooted in thermodynamics.

The working principle of a heat exchanger is based on the transfer of thermal energy from a hotter fluid to a cooler fluid across a solid conductive barrier—typically metal—without the fluids mixing. This heat transfer occurs via conduction through the barrier and convection within each fluid stream, following the Second Law of Thermodynamics, which states that heat flows naturally from hot to cold.

This seemingly simple principle underlies the design of over a dozen heat exchanger types, each tailored to maximize this energy transfer in different operating environments.

Heat exchangers mix hot and cold fluids to transfer heat.False

Heat exchangers transfer heat without mixing the fluids by using a solid barrier, such as a tube wall or plate surface.

The Heat Exchange Process: Step-by-Step Breakdown

- Two fluids (hot and cold) enter the exchanger in separate flow paths

These can be gases, liquids, vapors, or a combination (e.g., condensing steam vs. cooling water). Fluids are kept physically separated by a conductive barrier

This is usually metal tubing, plates, or channels that conduct heat efficiently.Heat flows from the hotter fluid to the cooler one through the barrier

This process involves:

- Convection inside each fluid (heat to/from surface)

- Conduction through the metal wall

- Overall heat transfer defined by the heat transfer coefficient (U)

- Neither fluid mixes, but the cooler fluid absorbs the heat

This raises the temperature of the cold fluid while cooling the hot fluid.

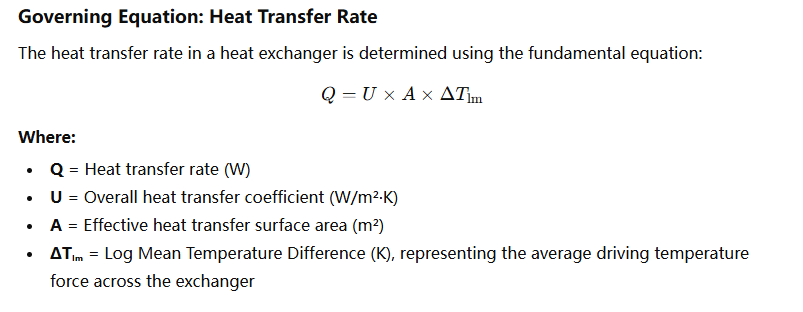

Governing Equation: Heat Transfer Rate

Common Flow Arrangements

| Flow Pattern | Description | Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Counterflow | Fluids move in opposite directions | Highest |

| Parallel Flow | Fluids move in the same direction | Moderate |

| Crossflow | Fluids move perpendicular to each other | Variable |

| Multipass | Fluids make multiple passes to increase contact | High |

✅ Counterflow is the most efficient pattern because it maintains a larger temperature difference throughout the exchanger.

Typical Components of a Heat Exchanger

| Component | Function |

|---|---|

| Shell or Plates | Outer housing that holds fluids or bundles |

| Tubes / Plates | Conductive pathways for fluid and heat |

| Baffles | Guide flow to improve turbulence and transfer |

| Nozzles | Inlet and outlet for each fluid |

| Gaskets/Seals | Prevent cross-contamination between fluids |

| Headers | Distribute flow into multiple paths (tube side) |

Working Principle by Heat Exchanger Type

| Type | How Heat Transfer Happens |

|---|---|

| Shell & Tube | One fluid flows inside tubes, one around tubes in shell |

| Plate (Gasketed) | Fluids flow in alternate plates, transferring heat through plates |

| Hairpin | Hot and cold fluids pass in opposite directions in long straight tubes |

| Air-Cooled | Hot fluid inside finned tubes, air blows across to remove heat |

| Double Pipe | One fluid flows in inner pipe, the other in the annular space |

Real-World Example

Application: Cooling hot oil from 180°C to 90°C using water

Heat Exchanger Type: Shell & Tube

Process:

- Hot oil enters the tube side

- Cool water flows in counterflow through the shell

- Heat transfers from the oil through the tube walls to the water

- Oil exits cooler, water exits warmer—without mixing

Summary Table: Key Concepts

| Principle Element | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Heat transfer medium | Metal surface (tube, plate, shell) |

| No fluid mixing | Fluids stay in separate paths |

| Driving force | Temperature difference between fluids |

| Governing law | Second Law of Thermodynamics (heat → cold) |

| Design factor | Surface area × flow rate × heat coefficient |

Conclusion

The core principle of a heat exchanger is simple: transfer heat from one fluid to another through a barrier, without mixing. Yet, the engineering behind achieving efficient, safe, and durable heat transfer—especially in industrial environments—is complex and requires precise understanding of thermodynamics, fluid mechanics, and material science.

💡 Every heat exchanger design, no matter how advanced, is just a smarter way to move heat from hot to cold.

Heat exchangers always require a power source to transfer heat.False

Heat exchangers operate passively using thermal gradients, not external energy sources for heat transfer. However, pumps or fans may move the fluids.

References

- Heat Exchanger Basics – How They Work – Thermofin

- Understanding Heat Exchangers – Engineering Toolbox

- Working Principles of Heat Exchangers – Exchanger Industries

- Heat Transfer Fundamentals – Khan Academy